TTUHSC Researcher Modifies Antibiotic to Treat Alcohol Use Disorder

Over the last decade, headlines across the U.S. have been dominated by the national opioid epidemic, and rightfully so. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 47,600 people died from opioid overdoses in 2017 alone, and more than 17,000 of those deaths involved prescription opioids.

As staggering as those numbers are, Susan Bergeson, Ph.D., a professor of pharmacology and neuroscience for the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) School of Medicine, said there is another substance-related issue that began plaguing society long before the arrival of the opioid epidemic: alcohol use disorder. Similar to the opioid crisis, Bergeson said the consequences of alcohol use disorder are not borne only by the patient. The disease also affects their family, friends and community.

“We’re seeing how horrific the opioid epidemic is, but for years and years alcohol use disorder has caused as much or more damage and cost than opioids,” Bergeson said. “In fact, five percent of all health disparities are related to alcohol. It's a $250 billion-a-year problem to society, which is more than all the money paid to buy the alcohol in the first place. It's a big deal, and if it's your loved one, it’s also personal.”

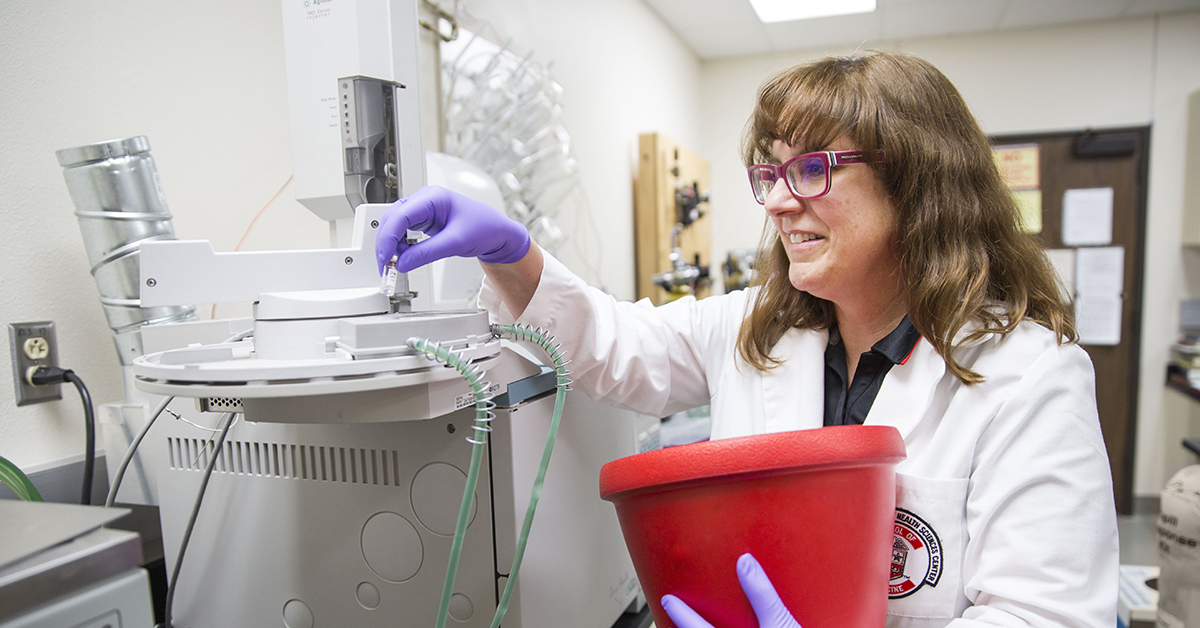

Bergeson is currently leading an effort at TTUHSC to develop a treatment for alcohol use disorder that uses a modified version of minocycline, a tetracycline antibiotic commonly used to treat illnesses such as pneumonia, acne and sexually transmitted infections.

Tetracycline antibiotics include a number of antibiotic compounds that share a common structure. They can be produced using specific bacteria known as Streptomyces, or semi-synthetically using other tetracycline antibiotics.

In earlier studies, some conducted by Bergeson and her collaborators and some by other scientists, the process of how alcohol acted in the body and how alcohol use disorder was conveyed appeared to be related to neuroinflammation. That caused researchers who had previously focused their efforts on neurotransmitter receptors, transporters and channels to take a new approach to study alcohol action on the innate immune system.

“It was really the first time that we all stopped and saw that we were finding similar kinds of things in the field,” Bergeson said. “A collaborator and I sat down and said, ‘What is currently known to target inflammation?’ So we simply searched for known anti-inflammatory and anti-immune acting drugs that were already available. It turns out that minocycline had been shown at the time to have some anti-inflammatory properties, so we decided to test the hypothesis that minocycline would reduce traits related to alcohol use disorder due to its ‘off target’ anti-inflammatory properties.”

After more research that included testing a series of seven tetracycline antibiotics in mice, Bergeson’s team discovered that some, including tigecycline, minocycline and doxycycline reduced drinking while the others did not.

Because chronic alcohol drinkers experience what is known as a leaky gut syndrome, which occurs when bacterial proteins in the stomach leak out and stimulate an immune response, Bergeson said they began looking at whether or not the antibiotics would create a similar reaction in the gut and adversely affect gut microbiota, which are the various microorganisms that live in the human digestive tract and play an important in one’s overall health. When they discovered this wasn't how the antibiotics were working, they started investigating the brain as the potential site of action for the antibiotics.

They began by introducing tigecycline directly into the brain of mice. Bergeson said they used tigecycline because it had some properties that minocycline and doxycycline didn’t have, which made it better experimentally at the time. They discovered that when tigecycline was placed directly into the brain, it reduced drinking while having no ability to kill microbes in the gut or in other peripheral areas of the body.

“Then we thought we needed to get rid of the antibiotic properties, because they cause several negative side effects,” Bergeson said. “For example, kids who have strong acne take minocycline for long periods of time, and while it's fairly safe, it’s not without its problems. You're more susceptible to viral infections, it disrupts your GI tract and there's tinnitus in your ears on occasion. So we thought we would modify the molecular structure and remove the antibiotic properties.”

Using data from previously published research that had solved the crystal structure of minocycline, tigecycline and tetracycline, the Bergeson team began the task of modifying the molecules of each. The process yielded several compounds that lost their anti-microbial action entirely. Bergeson said that even when these compounds are administered at very high doses, they don't kill bacteria and they retain their ability to reduce alcohol consumption. Several of the compounds also reduced alcohol withdrawal symptoms, which she considers to be an important benefit.

“Alcohol withdrawal can be a medical emergency,” Bergeson said. “Right now, when a person goes into detox, they are given benzodiazepines (tranquilizers), but those are co-addictive with alcohol. They suppress withdrawal symptoms, but that doesn't necessarily help treat the addiction process. However, the molecule we've developed could not only potentially help you make it through withdrawal without having seizures, but it would help you to reduce your cravings or your chronic desire to use alcohol.”

The immune system is functionally different in males and females. Because of this difference, pain is modulated differently in men and women, and alcohol has been shown to be far more damaging in females than males, even at the same blood alcohol concentration.

“In the first paper we published, the dose response is a little bit different; it's a little flatter in females,” Bergeson said. “Minocycline works a little bit better to reduce drinking at higher doses in males and females, but it still helps both. It blocks pain in males, but in our limited experiments with inflammatory pain, it actually did not help pain in females.”

When her team reaches a point where they can conduct human clinical trials with their lead compound, which is produced by modifying minocycline molecules, Bergeson thinks they may find there are both emotional and physical pain attributes associated with going through withdrawal that the new minocycline analog may provide more relief to males than females.

“There might be a co-therapy that needs to be applied to make the treatment work better in females, and there are pain researchers working on that now,” Bergeson said. “Obviously, the lead compound will be one that works as well in both sexes, though maybe not equally at the same dose, and the plan is to test it in humans when we get an FDA approval to use it as an investigational new drug.”

As her research continues, Bergeson said her team’s goal is to test whether or not one could go through withdrawal as an outpatient and have the prescription on hand so they can take the medication as they detox. Then, months or years later if the patient experiences a trigger that causes them to crave using alcohol again, they can take the medicine to avoid a relapse.

“Hopefully it will be similar to carrying nitroglycerin around for your heart because you’ll only take it when you need it,” she said.

Despite showing promise, Bergeson said the compound produced by her team’s work can’t, and shouldn’t be viewed as a cure because alcohol use disorder typically either causes, or is preceded by psychological events that have created difficult issues in the patient’s life and in the lives of their family and friends.

“The hope would be that we’re going to give you a medication that's going to help you, but I don't like to suggest it’s a cure,” Bergeson said. “We're going to provide a pill to reduce your desire to drink alcohol, but for better likely success, each patient should couple that treatment with counseling to deal with the emotional issues that either preceded or were a consequence of the alcohol use disorder.”

Related Stories

Celebrating Veterans: TTUHSC’s General Martin Clay’s Legacy of Service and Leadership

From his initial enlistment in the Army National Guard 36 years ago to his leadership in military and civilian health care management roles, Major General Martin Clay’s career has been shaped by adaptability, mission focus and service to others.

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Nursing Named Best Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program in Texas

The TTUHSC School of Nursing Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program has been ranked the No. 1 accelerated nursing program in Texas by RegisteredNursing.org.

TTUHSC Names New Regional Dean for the School of Nursing

Louise Rice, DNP, RN, has been named regional dean of the TTUHSC School of Nursing on the Amarillo campus.

Recent Stories

The John Wayne Cancer Foundation Surgical Oncology Fellowship Program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Announced

TTUHSC is collaborating with the John Wayne Cancer Foundation and has established the Big Cure Endowment, which supports the university’s efforts to reduce cancer incidence and increase survivability of people in rural and underserved areas.

TTUHSC Receives $1 Million Gift from Amarillo National Bank to Expand and Enhance Pediatric Care in the Panhandle

TTUHSC School of Medicine leaders accepted a $1 million philanthropic gift from Amarillo National Bank on Tuesday (Feb. 10), marking a transformational investment in pediatric care for the Texas Panhandle.

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Permian Basin Announces Pediatric Residency Program Gift

TTUHSC Permian Basin, along with the Permian Strategic Partnership and the Scharbauer Foundation, Feb. 5 announced a gift that will fund a new pediatric residency.