Music and Language Studies Intersect in the PeARL

As part of Texas Tech University's J.T. & Margaret Talkington College of Visual & Performing Arts(TCVPA), students, faculty and staff in the School of Music, the School of Art and the School of Theatre & Dance conduct performances, host exhibitions and lead projects and initiatives that enrich the community through the arts.

In the TCVPA's Performing Arts Research Lab (PeARL), directed by School of Music professors David Sears and Peter Martens, they also conduct groundbreaking, interdisciplinary research. The PeARL combines the arts with other fields of study in Lubbock and around the world like medicine, education, linguistics and psychology, to name a few.

Researchers involved in one of those collaborative projects, "Does order matter? Music and language processing deficits in individuals with aphasia," hope to make a difference in the lives of stroke patients. The project is funded by an Arts in Medicine grant from The CH Foundation and will use musical stimuli to treat aphasia, a disorder that impairs a person's ability to speak and understand others.

"Our goal in this research is to determine whether language and music share neural resources in brain regions that tend to be associated with language perception and production," said Sears, the principal investigator (P.I.) on the project. "To that end, we elected to study a population of people with pronounced language processing deficits – an impairment known as aphasia – to see if they demonstrate coincident deficits in the perception of music.

"If we use similar brain regions to process both language and music, and if people with aphasia demonstrate only partial deficits in music processing relative to language processing, it might be possible to use music as an intervention strategy in the aphasic population. The idea would be to show that music processing can bootstrap language processing."

The collaborators

Sears said a project of such interdisciplinary scope requires collaborations from

across Texas Tech and beyond. The team includes Texas Tech's TCVPA and the Department

of Psychological Sciences in the College of Arts & Sciences, the Texas Tech University

Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) and the College of Behavioral & Social Sciences at

the University of Maryland.

L. Robert Slevc, an associate professor and experimental psychologist at the University of Maryland, is co-P.I. on the project. Slevc, the director of the Language and Music Cognition Lab, has published a number of priming studies using both aphasic and neurotypical populations and said Sears contacted him about the project because of his interests in and previous research on the relationships between language and music and the deficits in each.

"My role is mostly on the theoretical end of things," Slevc said. "I've done a fair amount of previous work investigating if and how language and music processing are related, including some small-scale studies in aphasia. So I try to bring some useful ideas and advice to the project."

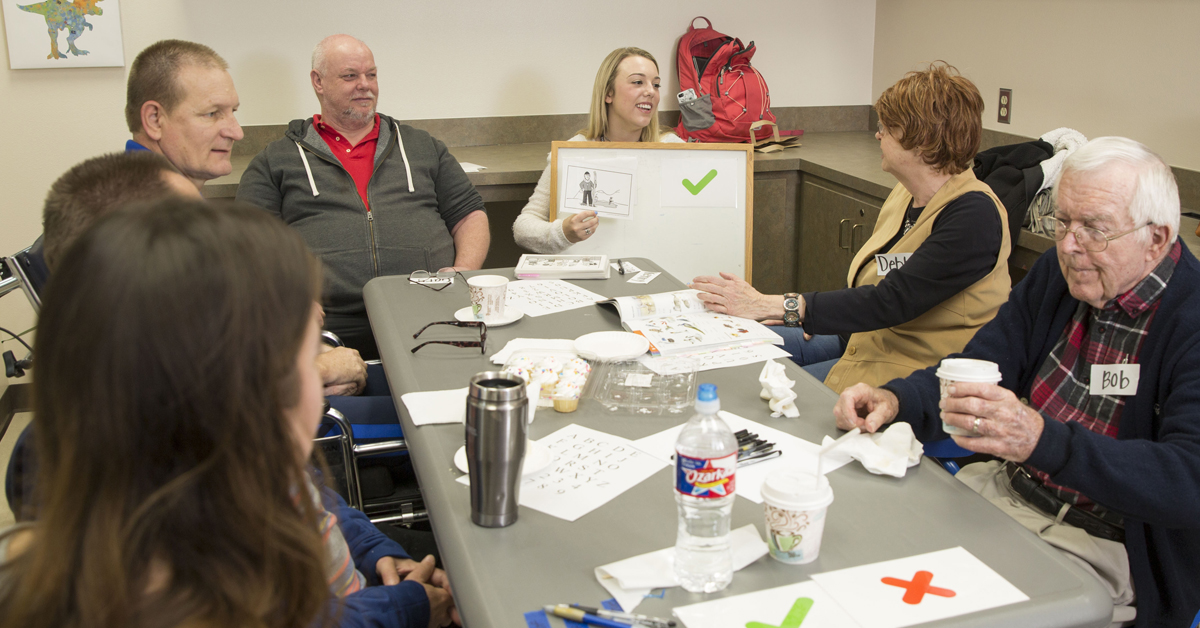

Sears also reached out to Melinda Corwin, a professor in the TTUHSC School of Health Professions and director of the Stroke & Aphasia Recovery (STAR) Program. The mission of the community outreach program is to maximize communication abilities and life participation for persons who are affected by aphasia and their families.

"I am interested in language production and processing and have worked with persons who have aphasia for the past 30 years," Corwin said. "I will serve as a consultant for the preparation of 'aphasia-friendly' testing procedures and materials and will assist in recruiting participants with aphasia for the research project. Dr. Sears and I have spoken several times, and we plan to meet this spring in preparation for protocol design, followed by participant recruitment and data collection."

The project also includes Texas Tech assistant professor Tyler Davis, director of the psychology department's Caprock FMRI Lab.

"Tyler Davis is a cognitive neuroscientist with considerable experience in behavioral and neural research methods relating to the study of learning and memory, both of which play an essential role in the present investigation," Sears said. "He is ensuring that the design of the behavioral experiments will permit planned follow-up studies using magnetic resonance imaging at the Texas Tech Neuroimaging Institute, the goal of which is to localize the brain regions responsible for the processing of language and music."

TCVPA Fine Arts Doctoral Program student Jonathan Verbeten, a research assistant responsible for designing the stimuli for the project, said working in the PeARL has shown him the university's commitment to this type of work.

"A project like this crosses several disciplinary boundaries and relies on the willingness of scholars and departments to work across fields," Verbeten said. "Texas Tech values and encourages interdisciplinary work, especially within the arts."

Conducting the research

Music, Sears said, is like language in that it is characterized by the ordering of

successive events. When listening to a chord sequence or a sentence, exposure to one

stimulus will inherently influence any stimuli that follow – the listener is primed

to recognize patterns and anticipate what comes next.

To study the effect of order on language processing, Sears said researchers sometimes employ a priming paradigm, which assumes that the speed with which a given word is processed is affected by the context in which it appears. Words that are related to the preceding events in the sequence will be primed, thus facilitating processing. It works the same for chords in a piece of music.

It's when these elements of a song or a sentence are out of order that issues arise.

"If you scrambled the order of chords in a familiar song, for example, listeners often struggle to identify the tune," Sears said. "The same is true for language, but in this case, scrambling the order of words in a sentence destroys the meaning of the sentence. In this project, we're designing a priming experiment where we scramble the order of chords in the preceding context to see if participants are slower to respond to the target chord in the scrambled condition compared to the unscrambled condition."

Participants, both musicians and non-musicians, will hear conventional chord sequences selected from the four-part chorales that either remain unchanged (strongly syntactic), or are scrambled to produce increasingly incoherent progressions (moderately or weakly syntactic).

"The scrambled sequences will be created using a probabilistic model that simulates long-term knowledge through unsupervised statistical learning of sequential structure," Sears said. "The model will learn the appropriate order of chords from a corpus of Johannes Sebastian Bach chorales analyzed by Jonathan Verbeten, and then produce scrambled versions of each stimulus that should be difficult for listeners to process."

Preparing the project

Much of the research in the aphasia project will center on the dataset and stimuli

Verbeten created by analyzing a large body of work by Bach.

"Past studies of this nature have written their own musical examples for stimuli," Verbeten said. "We wanted to conduct a priming study which used musical examples from real compositions. Our project relies on musical examples taken from Bach chorales."

Through harmonic analysis, Verbeten first reduced each chorale to a simple sequence of chords. He then stored each chorale in a computer database that encodes musical notation in a machine-readable format.

"The purpose of the computer database is to convert the chorales into a system which can then be analyzed through a parsing software in order to create a probabilistic harmonic model for our stimuli," Verbeten said. "In other words, through Bach's chorales, we can determine which combinations of chords are most likely to occur and contrast that with combinations which are least likely to occur.

"This is an important step in the project because we intend to organize our stimuli into categories of strong-medium-weak syntactical organization. By creating the probabilistic model, we can define these varying strengths based on analysis of Bach's compositions, not our own subjective assumptions."

Verbeten said being able to conduct the majority of his work in the PeARL has been beneficial in many ways.

"Among other reasons, it simply gives me a quiet place to work, which was ideal for

the analytical nature of creating the dataset," Verbeten said. "The PeARL will be

especially important in the next phase of the project when we bring in participants

for testing. We will have organized the stimuli into eight major and eight minor examples,

of which examples from the strong-medium-weak paradigm will be presented, and we will

ask

participants to identify whether or not the final note of the example is in or out

of tune."

Verbeten said it will be crucial for participants to be in a space where no distractions could tamper with their responses. Sears said the PeARL is equipped to not only provide that space, but also collect and analyze the data from the testing.

"We have a state-of-the-art sound attenuation booth that allows us to conduct auditory experiments in relative isolation," Sears said. "We also use specialized hardware and software to present media of various kinds, like images, videos and audio, and collect behavioral data from participants."

Making an impact

The research team continues to collect data and design the stimuli, with the intention

of conducting the initial behavioral studies this spring.

"We'll then design follow-up experiments using language stimuli," Sears said. "We'd also like to reproduce these experiments using FMRI to allow us to identify the brain regions responsible for language and music processing."

According to Slevc, the ways in which language and music are related, or not related, could have important implications for a broader understanding of how our brains and minds make sense out of sound. Most of the work that has been conducted in this area has been on a small scale and didn't involve such a wide range of experts, he added.

"Losing language abilities in aphasia can be devastating, and while there's some evidence that musical interventions might be helpful, there's not yet a good understanding of exactly why and how," Slevc said. "I know of no previous work that's really brought together expertise on music, cognitive science and aphasia treatment/recovery in this way, and I think it's really exciting. This work has potential to give the theoretical background that could lead to useful clinical therapies and strategies."

Corwin said the creation of additional successful therapy techniques could greatly improve the lives of those experiencing aphasia.

"Aphasia is a loss of language but not a loss of intellect," Corwin said. "Imagine waking up one day and no longer being able to speak, understand, read and/or write, but still being able to think as you always have. This is the experience of a person who acquires aphasia, which happens suddenly and without warning due to a stroke or brain injury.

"Research studies that contribute to increased understanding of the condition of aphasia and how to treat it benefit persons with aphasia, their family members and professionals who work with them. Our ultimate vision is communication access for all. This is an exciting time for Texas Tech, TTUHSC and all of the persons with aphasia we serve."

Related Stories

How Does Your Garden Grow?

As spring approaches, some people’s thoughts turn to gardening. Whether it’s a flower garden they desire or a vegetable garden want to have, they begin planning what they’ll plant and what they need to do to ensure a successful garden.

Adopt a Growth Mindset for a Better Life

A “growth mindset” accepts that our intelligence and talents can develop over time, and a person with that mindset understands that intelligence and talents can improve through effort and learning.

Drug Use, Family History Can Lead to Heart Disease in Younger Adults

Abstaining from drug abuse and an early diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol) can help prevent heart disease.

Recent Stories

TTUHSC, TTU School of Veterinary Medicine Recognize Student Research During Inaugural Amarillo Research Symposium

More than 100 student and trainee researchers from the TTUHSC and the TTU School of Veterinary Medicine presented research findings at the 2024 Student Research Day on April 19.

The TTUHSC Laura W. Bush Institute for Women’s Health Welcomes Ben Carson as Power of the Purse Keynote Speaker

Retired neurosurgeon and former U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson, M.D., delivered a keynote address at the Power of the Purse luncheon and fundraiser today (April 18).

Filling the Gap: PA Impact on Rural Health Care

Assistant Professor and Director of Clinical Education Elesea Villegas, MPAS, PA-C, spoke about the challenges rural health care currently faces and how PAs are stepping up to better serve the rural patient population.